Views: 0 Author: Site Editor Publish Time: 2025-12-09 Origin: Site

Accidents from uncontrolled energy still injure thousands of workers every year. Machines store power in ways people often overlook—springs, pressure lines, moving parts, hot surfaces. When these systems release energy suddenly, it can crush, cut, burn, or kill.

OSHA created the Lockout/Tagout rule to stop these incidents. This guide explains everything in plain language—what the rule says, how to follow it, and why so many companies still receive citations.

Lockout/Tagout is a safety method that prevents machines from starting, moving, or releasing stored energy while someone is repairing or maintaining them. It acts as a physical and visual barrier that tells workers, “This equipment is not safe to operate right now.”

It uses two essential components:

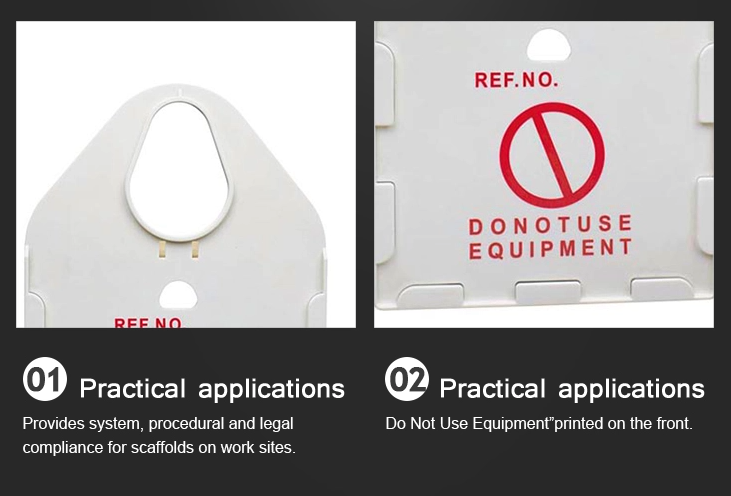

Lockout – a physical device, such as a padlock or valve lockout, that directly blocks energy from flowing or parts from moving. Once applied, the equipment cannot operate until the person who installed the lock removes it.

Tagout – a bright, highly visible tag attached to equipment that warns others not to start or use it. Tags provide information but do not physically stop the machine.

Although the two methods sound interchangeable, they provide different levels of protection. A tagout device relies on workers paying attention, while a lockout device creates a physical barrier. That’s why OSHA requires companies to use lockout whenever a machine can accept a lock.

Together, lockout and tagout form a layered system that reduces human error and prevents accidental energization.

Hazardous energy isn’t just electricity. Modern machinery stores power in many ways, and each one can injure or kill if released unexpectedly. Workers often underestimate how much energy a machine can retain even after it’s powered off.

Common types include:

Electrical power – energized circuits, capacitors, backup batteries

Hydraulic pressure – fluid-filled lines used in lifts, presses, and molding machines

Mechanical tension – springs, belts, moving arms, counterweights

Pneumatic air pressure – compressed air used for clamps, actuators, or cylinders

Chemical reactions – stored gases, corrosive fluids, fuels

Thermal energy – heat in ovens, heaters, molding equipment, or hot pipes

Any machine may combine several energy types at once. For example, a press may use electrical controls, hydraulic cylinders, pneumatic clamps, and mechanical springs.

Because of this complexity, LOTO procedures require methodical steps to ensure every energy source is addressed, verified, and safely controlled before work begins.

OSHA’s Lockout/Tagout rule is found in 29 CFR 1910.147, commonly called The Control of Hazardous Energy Standard. It establishes the minimum requirements employers must follow to isolate energy and prevent accidental startup.

This standard applies to a wide range of workplaces where machines require servicing, including:

Machine shops

Fabrication and welding facilities

Packaging and bottling lines

Assembly plants

Metalworking and CNC machining centers

Warehousing facilities with automated machinery

Although the rule targets general industry, OSHA also enforces 29 CFR 1910.333 for electrical work, which outlines how to de-energize and safely work on electrical circuits. Construction, agriculture, and maritime industries may use modified versions of the rule, but the core principle remains identical: workers must not service equipment until all hazardous energy sources are fully controlled.

OSHA introduced the standard to address thousands of annual injuries caused by machines that started unexpectedly. Over time, industrial equipment has grown more complex, which makes consistent LOTO practices even more important. Multi-source energy systems, automation, robotics, and advanced control circuits all increase the need for clear, standardized procedures.

Even today, OSHA continues reviewing whether new digital lockout technologies—like eLOTO software, connected sensors, and robotics controls—should be formally included in future regulations. Until then, employers must follow the traditional requirements outlined in 1910.147 and document every step.

Over the past year, OSHA issued more LOTO violations than before. Many shops handle tight deadlines, new equipment, staffing shortages, and more complex machines. These issues increase human error.

OSHA repeatedly cites companies for:

| Violation Type | Description | Why It Happens |

|---|---|---|

| Missing procedures | No written steps for shutting machines down | “We know how to do it” culture |

| Poor training | Workers don’t understand roles or hazards | High turnover, rushed onboarding |

| Lack of inspections | Annual audits never documented | Managers assume things are fine |

| Wrong devices | Tags used where locks are required | Limited equipment or poor planning |

These areas create major safety gaps. OSHA fines can reach tens of thousands of dollars per violation.

OSHA expects employers to build a complete energy-control system—not just locks, tags, or scattered instructions. A real LOTO program works like a chain. If one link weakens, the entire system becomes a risk. The standard in 29 CFR 1910.147 explains what every facility must include and how workers should handle hazardous energy during maintenance or servicing.

This written program acts as the facility’s rulebook. It explains the types of hazardous energy present in the workplace and identifies which employees are authorized to perform lockout operations. It also outlines how lockout devices must be applied and removed, how shift changes should be handled, and how contractors must follow the same procedures as internal staff. A clear written plan removes guesswork and ensures everyone works from the same instructions instead of relying on memory or improvised steps.

Each machine must have its own detailed lockout procedure because every piece of equipment stores energy differently. These procedures describe the correct shutdown method, list every isolation point such as valves and disconnect switches, and explain how to release any stored energy inside the system. They also show workers how to verify that the machine cannot restart once it is locked out. Many facilities include diagrams or photos to help workers locate energy points faster, especially on complex or multi-energy equipment where electrical, pneumatic, and mechanical forces coexist.

OSHA requires lockout devices to be durable, standardized, and easy to identify. In practice, this means companies must use locks and lockout hardware that stand up to harsh conditions, can be recognized at a glance, and remain consistent across departments. Common solutions include padlocks, valve lockouts, plug lockouts, cable systems, and group lock boxes. These devices need to match the equipment they secure, and only trained personnel are allowed to install them. Many companies also assign specific lock colors or labels to make it clear who controls each device.

The lockout sequence must always follow a defined order. Workers begin by notifying others in the area, then shut down the machine using its normal controls. They isolate every energy source, apply the proper lockout devices, release any stored pressure or tension, and test the system to confirm it is safe. Maintenance begins only after the machine is fully verified. When the work ends, the person who placed the lock must remove it; OSHA only allows alternative removal methods in very limited, controlled situations. Shift changes need careful handoff procedures so machines do not become energized by mistake.

OSHA divides training into three groups because each group interacts with hazardous energy in a different way. Authorized employees learn the full lockout procedure, including how to isolate energy and test equipment. Affected employees work near the machines but do not perform lockout, so they need to understand what a lock or tag means and why they must not restart the equipment. Other employees in the area must learn to recognize lockout devices and avoid disturbing them. Training repeats when equipment changes, when procedures update, or when audits show unsafe behaviors. Hands-on practice often helps workers build confidence and avoid mistakes.

Every year, facilities must inspect their entire lockout program to make sure procedures still match the equipment and that employees follow the steps correctly. During an audit, a supervisor or experienced employee reviews written procedures, watches real lockout tasks, checks the condition of devices, and identifies any unsafe habits. The findings must be documented, including who performed the audit, which machines were inspected, and what corrections were made. Many facilities perform extra audits after installing new machinery or after incident reports, using the audit as a tool to strengthen overall safety.

Many workplaces assume a bright caution tag offers enough protection. It doesn’t. Lockout and tagout serve two very different roles, and OSHA makes that distinction clear because the level of protection they provide is not the same.

Lockout uses a solid, physical device—usually a padlock or a specialized lockout tool—to stop a machine from moving or energizing. When a machine can accept a lock, OSHA expects companies to use this option because it gives the highest level of safety. A locked valve, switch, or breaker can’t be turned on accidentally, and it removes much of the uncertainty that leads to injuries. Workers trust lockout because it provides a real barrier between them and hazardous energy, not just a reminder.

Tagout works differently. Instead of blocking motion, it warns workers not to start the equipment. A tag is only a communication tool, not a physical barrier. OSHA allows tagout only when a machine cannot be locked out, and even then it must provide “equivalent protection”—a standard that is extremely hard to meet in practice. Tags can tear, fall off, or be ignored, especially in loud or fast-paced environments. Because it relies entirely on human judgment, tagout is the weaker option, and most facilities use it only when no lockout point exists.

The big takeaway? Workers need lockout whenever possible. It removes doubt, reduces human error, and gives employees something solid to rely on instead of a warning sign.

Factories use more robots, CNC systems, and digital controllers than ever. With this shift, OSHA began studying whether traditional LOTO rules need updates.

Companies try digital tools such as:

Mobile apps for procedures

QR codes on machines

Online LOTO documentation

Electronic audit reports

But factories often face signal problems. Thick walls, long distances, and interference from heavy machinery can block Wi-Fi or Bluetooth. For that reason, most digital LOTO systems include offline modes. Still, electronics do not replace physical lockout devices. They only support the process.

Lockout tags are usually made of durable PVC, laminated plastic, or tear-resistant synthetic paper that withstands chemicals, moisture, and industrial environments.

Authorized employees are responsible for applying LOTO tags and locks, because they are trained to identify energy sources and verify safe shutdown procedures.

LOTO equipment should be inspected regularly, typically during annual energy-control audits or whenever devices show wear, damage, or fading.

LOTO procedures comply with OSHA requirements when they include written energy-control steps, employee training, periodic inspections, and the use of compliant lockout devices and tags.

A strong lock out tag out program doesn’t happen by accident. It grows from clear procedures, consistent training, and reliable devices that workers trust every single day. As machines become more complex and store more hidden energy, companies must stay disciplined and keep improving their LOTO systems. Small shortcuts can lead to major injuries, while simple habits—verify the shutdown, use the right lock, follow the written steps—protect everyone on the floor.

Many facilities choose partners who specialize in LOTO hardware because they want equipment that holds up under real industrial conditions. Lockey Safety Products Co., Ltd. supports that goal by providing durable lockout devices, standardized tags, group lock boxes, and full lock out tag out solutions designed for different machines and environments. Their products help teams stay compliant and make safety easier to manage, even in busy or fast-changing workplaces.